Pleasant Pastures Seen?

What does the

government’s Land Use Framework promise?

Will profit win over nature and agriculture?

Or can the government finally create a

joined up approach to land use

that ensures a secure, healthy and resilient future for all?

Source: www.gov.uk

Criticism

As with every new government plan, it is not without

criticism. The overriding concern is about putting profit first, when perhaps the

real emphasis should address the needs of the land first. ‘You cannot have

economic prosperity when nature is on its knees,’ says the passionate President of the CPRE, Mary-Ann Ochota. Growth now, nature later simply doesn’t work.

Will the framework really have nature’s back?

The National Farming Union (NFU) is up in arms over the

Inheritance Tax announced last year but they have managed to put together a

blueprint that they hope will play an important role in the framework. “Agriculture, and the farmed environment, is being

short-changed by the planning system. That must end with government matching

its rhetoric with action when it comes to planning reform,” said the

exasperated NFU President Tom Bradshaw at the opening of their annual

conference on Tuesday 25th February 2025.

Sarah Cowie, Senior Policy Manager for Climate Land and

Business at the Scottish NFU was interviewed on BBC Farming Today earlier this

month about the success of Scotland’s Land Use Strategy which is mid-way

through its third edition (2021-2026). She warned that the Scottish NFU had

hoped that the strategy would make hard decisions more straight forward and

that whilst the vision was to be applauded, a pathway is needed for on the

ground action in order to guide the country to a state where agriculture, food

production, biodiversity, climate mitigation and people are better integrated when it comes to policy decisions.

Conclusions

The framework needs to consider these criticisms and the insights

gained from the North. This consultation

presents a vital chance for us to express our views and to ensure that it can

deliver a sustainable future for communities, agriculture and the environment. Without

a solid framework in place, we will be left with contradictory regulations that

result in hasty decisions that fail to tackle the long-term issues at hand.

This is our moment to create sustainable

land management policies that could even streamline the planning process. We

must prepare the land for the impacts of climate change. We must provide the

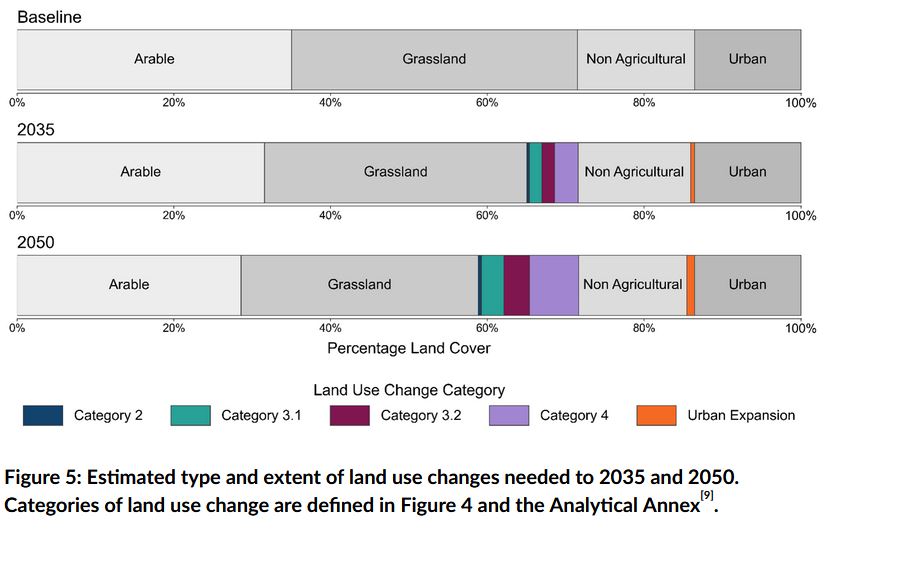

right incentives for landowners so that the land use change happens in the

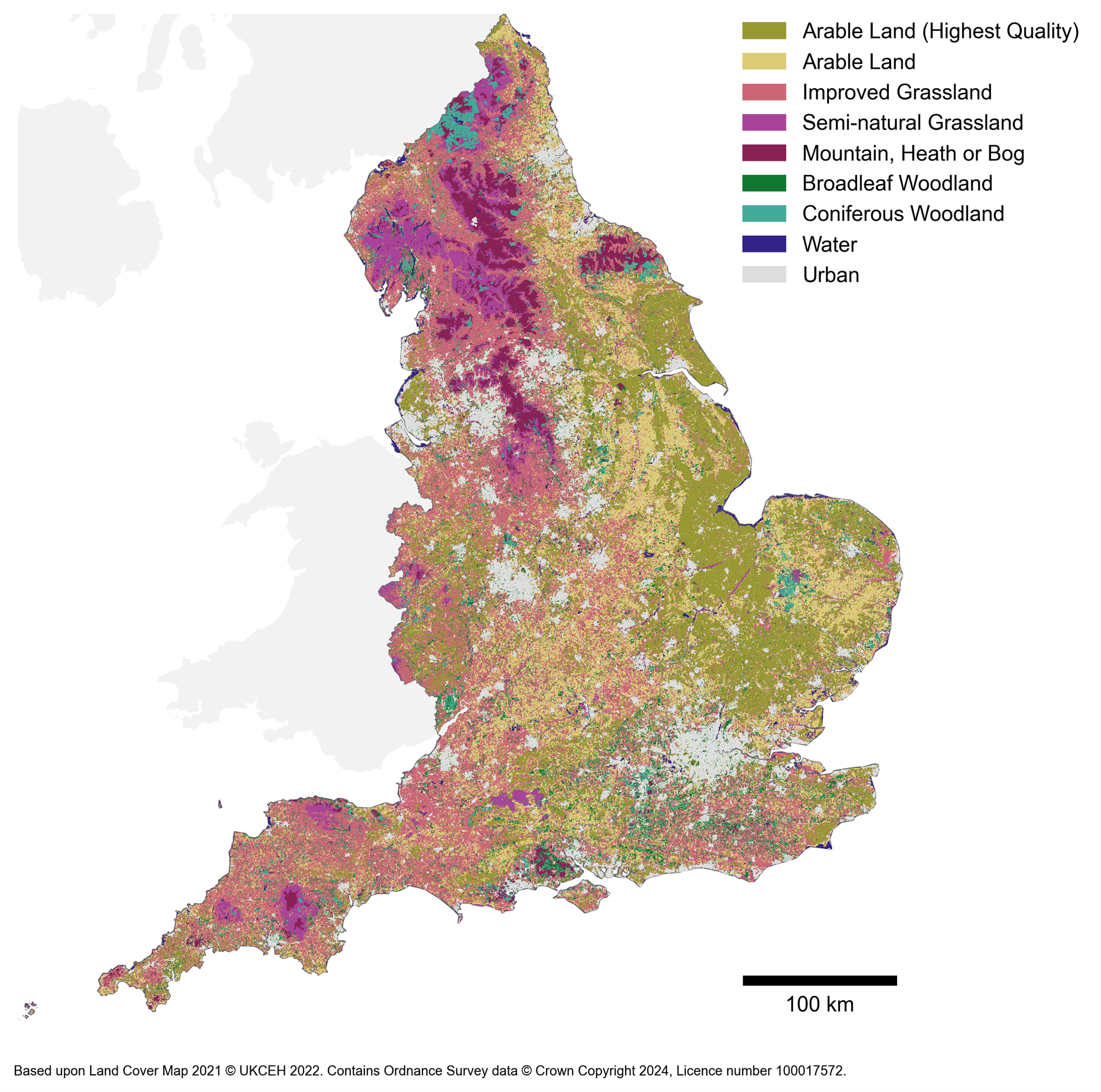

right spaces. Keeping spatial data up to date is essential; otherwise – what is

the point?